Coke & Rachmaninov

An exploration of the great Russian composer's influence on his English friend.

Roger Sacheverell Coke was an ardent supporter of underrated composers and alongside his performing career gave presentations and lecture-recitals to promote Mahler, Bruckner and others, also citing Arnold Bax as hugely influential on his own writing. From an early age he was an admirer of Sergei Rachmaninov and his music was frequently compared to the Russian master. Determined to promote Rachmaninov’s works - we must remember that in the first half of the twentieth century Rachmaninov's music certainly did not enjoy the popularity it boasts today - Coke often wrote in journals urging musicians and promoters to consider performing Rachmaninov's music:

...Rachmaninov’s ‘Chopin’ Variations (Op. 22) for piano solo. May I heartily endorse this, as it is one of his noblest and most characteristic works, and at the same time one of the most neglected. The two piano sonatas are also fine and should be far better known; I have had both privately recorded by Charles Lynch, who also broadcast the first sonata... The Corelli Variations are less in need of advertisement. [Gramophone, date unknown]

...In saying that this composer’s [Rachmaninov’s] Second Symphony is “no more a répertoire piece than ‘The Bells’ or the Fourth Concerto”...Mr. Lyle forfeits any serious claim he might have had to be considered even as a letter writer on this subject. [Musical Opinion, 1941]

Coke visited Rachmaninov twice in Lucerne and is quite likely the Rachmaninovs visited Brookhill Hall too when in the UK for a concert tour. Oh, if only I could finally find the Visitors Book! Coke dedicated his Second Symphony to Rachmaninov (with his permission), and his continued adoration permeated much of the English composer’s own work.

I want to explore this connection further. What better place to start than the work Coke described as his finest, the Concerto No.3 in E flat Op. 30 (1938)? The critic for Musical Opinion certainly heard the influence of Rachmaninov at a performance of the work in June 1962:

It is strongly influenced by Rachmaninoff, when the composer gets hold of a good idea he hammers at it mercilessly, the formal joints sometimes creak a little, and so on. But I suppose we could say much the same of the Rachmaninoff No. 2 – and that has not been exactly unpopular!

Indeed, my own recent performances and recordings of Coke have drawn similar – unprovoked – reactions:

[Coke’s] more than half an hour-long Variations & Finale Op. 37 is a noble and solemn piece in the tradition of Rachmaninov. [Kieler Nachrichten, August 2016]

It seems to be a dark and faded Rachmaninov, suffocated by Coke’s own melancholia. [Musica, December 2015]

Let’s return to the concerto. Aside from some obvious elements which are undoubtedly rooted in the tradition of Russian romantic concertos – the rich orchestration, the prominence and virtuosity of the piano part in all the thematic material, the expressive woodwind solos – Coke also quotes Rachmaninov on at least two occasions during this work.

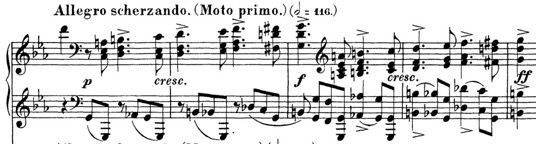

I couldn't help but notice the striking similarity of these two passages, for example, the first is from the finale of Coke's third concerto, the second from Rachmaninov's No. 2, Op. 18 (1901):

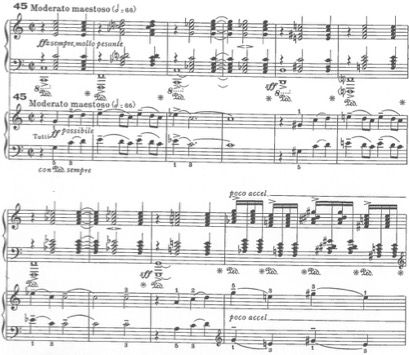

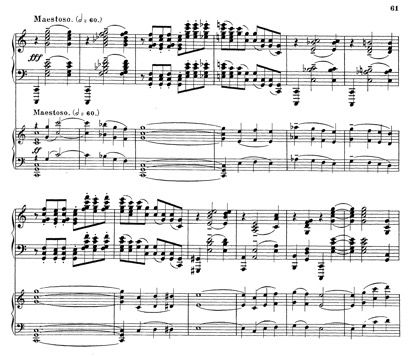

And the famous epic ending of Rachmaninov’s 2nd Concerto with that unashamedly Russian melody played by the full orchestra with crashing, triumphant chords from the pianist, was unarguably the inspiration behind the closing section of Coke’s own work (again Coke's extract first, followed by Rachmaninov's version):

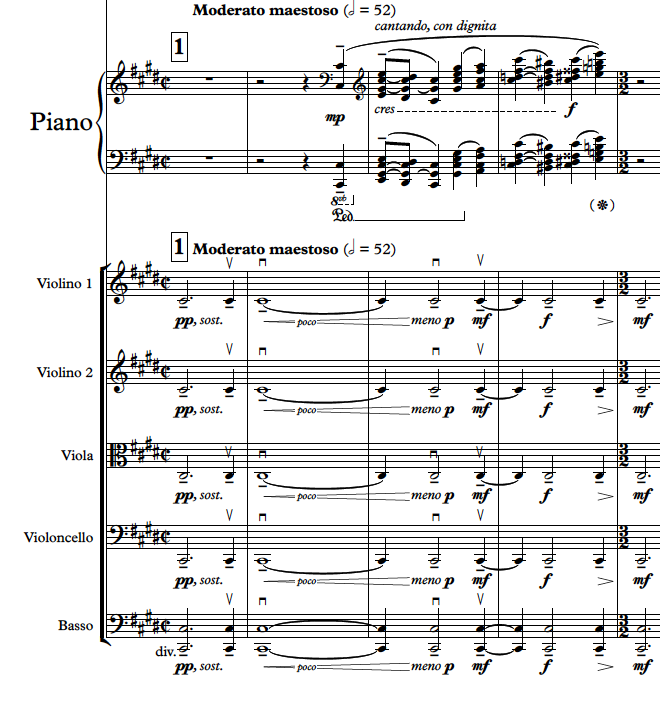

Whether these were conscious quotations or perhaps that Coke was simply so deep into the musical world of Rachmaninov that he inadvertently assimilated some of the most compelling elements of the music remains an unanswered question and one for further debate, but let me present one final example. This time the 4th concerto – what a gasp came from the lovely musicians of the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra at our first rehearsal on this piece! The sombre mood, the minor tonality and at least the first four notes of the melodic line cannot help but bring to mind the iconic opening of Rachmaninov's D minor Op. 30:

I should say that although the influence of Rachmaninov was certainly hanging over Coke for perhaps his entire compositional career, that isn’t the full story. In my next blog post, I will explore Coke’s own unique musical voice, and more about what drew me to this intriguing music.