Please join me at Wigmore Hall on 3 Feb!

Cyril Scott's First Sonata in Context

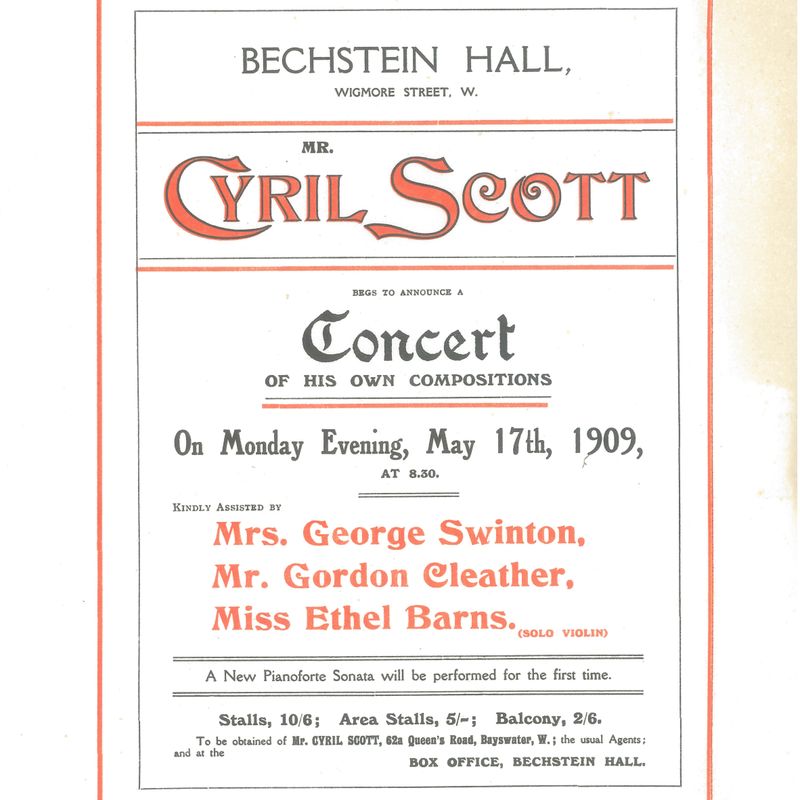

Cyril Scott was a pianist-composer with a strong link to Wigmore Hall. He premiered his First Sonata Op. 66 at Bechstein Hall on 17 May 1909. The programme for my Wigmore Hall recital on 3 February 2024 sets this large-scale 20th century piano sonata in the context of composers who influenced and were admired by Scott.

Some Thoughts on Cyril Scott

Cyril Scott was admired by composers as diverse as Claude Debussy, Richard Strauss, Igor Stravinsky and his lifelong friend — Percy Grainger. He was part of what became the 'Frankfurt Group' following his studies there in 1905 alongside the other members: Roger Quilter, Balfour Gardiner, Norman O'Neill and Percy Grainger.

'one of the rarest artists of the present generation...His music unfolds itself somewhat after the manner of those Japanese Rhapsodies which are the outcome of imagination displaying itself in innumerable arabesques, and the incessantly changing aspects of the inner melody which are an intoxication for the ear, are, in fact irresistible'. [Debussy]

'Cyril Scott [wrote Percy Grainger] composes rather as a bird sings, with a full positive soul behind him, drawing greater inspiration from the mere physical charm of natural sound, than from any impetus from philosophical preconceptions or from the dramatic emotion of objective life'.

Eugene Goossens, another admirer of Scott, claimed that he was almost the first composer in Britain to assimilate the characteristics of the French style and shape them to his own devices. Meanwhile Michael Hurd, in his article for the Grove Dictionary in 1980, wrote that:

'The rich harmonies, the languorous melodic lines and the rhapsodic diffuseness of form that had once seemed daring and very un-English, came to be regarded simply as part of a period tendency which had seen its most successful expression in the music variously of Debussy and Skryabin'.

On Scott's First Sonata Op. 66

’In his development of irregular rhythms’, said Sir Thomas Armstrong, ‘[Scott] was a pioneer with Grainger and Stravinsky, for it is true to say that the two English-speaking composers were certainly not behind the Russian in such experiments’.

Ronald Stevenson, vice-president of the Grainger Society, tells us that Cyril Scott actually asked Grainger for permission to use the free rhythms and multiple time-signatures with which Grainger had been experimenting since 1900, in this sonata, which was ‘extensively played all over Europe’.

Cyril Scott himself (in his memoirs, 'Bone of Contention') wrote that:

'At the time of writing this chapter he [Grainger] is playing my Piano Sonata No.1 on tour – a work I wrote some forty-five years ago. With his characteristic over-generosity he declares in the programme notes: ‘In our own times the outstanding vehicle of musical progress has been the Cyril Scott Piano Sonata, Op.66, with its irregular rhythms (originally an Australian invention), its ‘non-architectural’ flowing form, its exquisitely discordant harmonies. The Scott Sonata is as significant artistically, emotionally and pianistically as it is historically…’. In this panegyric, however, he omits to mention that it was he himself who first gave me the idea of writing in irregular rhythms'.